Once you begin learning about plants, it’s hard not to fulfill that bone-deep temptation to run out and start picking them. After all, wildharvesting and foraging for food and plant medicine is something humans have been doing since time immemorial. It’s in our blood, whether we (consciously) remember it or not.

1

As another winter season melts away and the new green life of spring emerges, this temptation becomes even greater: Fresh shoots and spring flowers raise their sleepy heads, the ground once again feels like a living breathing being, and all around us life abundantly flows.

I believe harvesting and wildcrafting is our right as humans, but it also comes with a certain level of personal and collective responsibility. Just as you wouldn’t take a handful of random pills you find on the sidewalk, you also can’t run out and start picking and eating unknown plants.

2

As more people begin wildcrafting, we’re also seeing a number of plants becoming over-harvested, endangered, and in some cases— near extinct.

That’s why it’s so important to not only know what you’re harvesting, but to do so in a way that’s respectful of the land and the plants.

Here’s a beginner guide that will help you start your own safe and ethical wildcrafting practice.

Be 1000% sure what you’re harvesting ⍣

Yes, you read that right— one thousand percent. There are so many reasons you want to be that certain about the exact plants you harvest. For starters, you might pick a plant that’s endangered. There’s also a number of medicinal plants that have poisonous lookalikes.

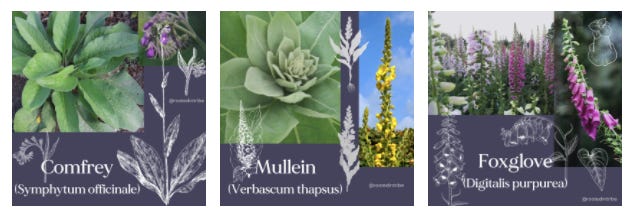

Plants may also look different from year-to-year and season to season, which can make proper identification that much harder. For example, some biennial3 plants (like mullein) don’t produce flowering stalks until the second year of life. Foxglove (which would stop your heart in minutes if ingested), may also appear with only its basal leaves (no flowers) in its first year— making it easy to confuse with more benign medicinal plants like comfrey and mullein.

You can mitigate these risks by taking the time to learn about the plants growing in your backyard.

Pick up a field guide specific to your region and prioritize learning how to identify any toxic or endangered species you may encounter.

Ask permission ⍣

Asking permission before harvesting is two-fold. First, you should always have the permission of whoever owns the land you plan to forage on. This might be an individual or an organization4. Another practice, which I try to embody whenever wildcrafting, is to ask permission from the plant.

This could be something you do on a spiritual level— sitting with the plant for a few minutes, saying a prayer of thanks, and listening to hear if the plant is open to being harvested.

If you’re not quite ready to start talking to plants (a practice I highly recommend), in the very least you’ll want to look at the plant be sure you won’t cause any unnecessary harm by harvesting from it.

Use your senses to determine if a plant is in a good enough state5 to be sharing its abundance with you. As an example, you shouldn’t harvest from plants that are injured or seem sick. Likewise with plants that are the only ones of their kind, ones that are endangered, or plants that seem like they’re struggling to survive.

You can practice this kind of observation by noticing trees shedding sap— which should only be harvested from the ground at the base of the tree, and never plucked directly from an open wound the tree is trying to heal.

A good rule of thumb is to only take 10% of a single plant or of a patch, to avoid causing undue harm.

Only take what you need ⍣

This is a big one. Spend some time before you go wildharvesting and think about what your goals are. Do you just want a bit of fresh plant material to make a tincture? Or some herbs to toss on a salad? Both of these things actually require very little plant material, and you won’t have to fill your basket very high before reaching a point of having taken too much.

Before harvesting anything, you should also consider how much time the processing of your herbs will take. Many herbs (such as roots or aerial greens) will need to be processed right away or they’ll become impossible to use.

Whether its cleaning and chopping roots into smaller pieces (which is required when harvesting roots that can harden within minutes of being plucked from the ground), or bundling and hanging herbs to dry (as you do with fresh leaves and aerial plant parts to avoid them going bad)—processing often takes at least three or four times as long as the actual harvesting.

Start small, take less than what you think you need, and be prepared to spend a few hours afterward processing your harvest so that it doesn’t go to waste.

Make offerings ⍣

Another thing many herbalists and plant folk do when wildharvesting is to make an offering. After all, this plant is giving you part (or possibly all) of itself and it’s important to recognize that sacrifice. Pour a little water from your bottle at the base of the plant you plan to harvest from, or leave a strand of your hair. Spend a moment thanking the plant for sharing its abundance with you.

Practice regenerative harvesting ⍣

As plant lovers, it’s always good to find ways to help your favorite wild plants thrive, even as you take parts of them back into your home. Here are some best practices to keep in mind:

Harvest in a way that’s good for the plant. When harvesting aerial parts of plants (like leaves), always leave enough behind so that the plant can continue the process of photosynthesis. When harvesting tree bark— cut off an entire branch of the tree and harvest all parts of the branch. Never cut bark off the main trunk of a tree, as you’re leaving it exposed to potentially harmful pathogens.

Replant those roots! If you’re harvesting an entire plant for its roots, you may have the option to take what you need and replant the crown6.

Know the optimal time of year to harvest. Plants draw energy down into their roots in the fall through early spring, making this the ideal time to harvest them. In warmer months, the aerial parts of the plant contain the most vitality. This is why you wouldn’t harvest flowers in late fall, or roots in the very beginning of summer.

Be discreet ⍣

There’s no nice way to say this: People are sheep. If they see you picking something, they might be tempted to join in. Always plan on harvesting in public places at less-trafficked times, and do so in a way that the next passerby wouldn’t be able to tell that anything had been taken. Leave the your harvest site as you found it (or better), and you’ll be well on your way to becoming the type of plant ally this world needs.

Botanical drawings by @kisstothka; Photos by Annie Spratt

As an Amazon Associate, I earn a small percentage from qualifying purchases made through this post.

Botanical drawing of Sage- Some species of this amazing plant (notably Salvia apiana, or White Sage) have been over-harvested for years.

Botanical drawing of Dill- (Anethum graveolens) a member of the Apiaceae (carrot) family. This family contains a number of edible plants, right alongside several deadly poisonous ones—notably Hemlock (Conium maculatum) and Water Hemlock (Cicuta douglasii). Whenever you see an umbrella-like formation on plants (called an umbel, hence the former plant family name Umbelliferae), be extra cautious you’re properly ID’ing it.

Biennial plants take two full years to complete their life cycle: From initial stages of growth (year one) to flowering, setting seed, and dying back (in year two).

Bear in mind that many indigenous cultures still use certain plants in sacred rituals and practices. Learn about the plants you intend to harvest in advance, and you’ll better understand what kinds of permission you need to obtain before harvesting.

Maximize your chances of finding healthy plants by not harvesting near roads (hello air pollution!), and or in places where pesticides have been used.

To replant a root crown, cut away the roots you intend you use, leaving at least a few white new rootlets and enough plant material for regrowth. This might mean trimming down the stalk of the plant to avoid overly-taxing the roots. Replant the crown at the same depth you found it.

This is so on top of every point! It’s not just going out and plucking some things! This is what it’s really all about!! Ha ha thank you for this!